Tell the Full Story

We believe all Americans deserve to see their history in the places that surround us. Yet just a small fraction of the sites on the National Register of Historic Places represent women and people of color. As a nation, we have work to do to fill in the gaps of our cultural heritage.

That’s why the National Trust for Historic Preservation shines a long-overdue spotlight on generations of trailblazers by saving the places where they raised their voices, took their stands, and found the courage to change the world.

Thanks to the support of people like you, we can tell a fuller American story. It’s a story that does justice to the contributions of women, people of color, and all Americans in shaping our nation and leading us forward. And it’s a story that stirs us all to take pride in our shared heritage and inspires us to create an even more perfect union for generations to come.

That’s why the National Trust for Historic Preservation shines a long-overdue spotlight on generations of trailblazers by saving the places where they raised their voices, took their stands, and found the courage to change the world.

Thanks to the support of people like you, we can tell a fuller American story. It’s a story that does justice to the contributions of women, people of color, and all Americans in shaping our nation and leading us forward. And it’s a story that stirs us all to take pride in our shared heritage and inspires us to create an even more perfect union for generations to come.

Our Stories

Native Americans on Bryan Neck

|

This marker stands on the bank of the Ogeechee River, just inside the entrance to Fort McAllister Historic Park located at 3894 Fort McAllister Road, in Richmond Hill, Georgia. More displays can be found inside the museum at Fort McAllister.

|

Across the Ogeechee River at Fort McAllister State Historic park was the northernmost town of the Province of Guale, the village of Satuache. Spanish records place Satuache about 10 miles northeast of Guale’s provincial capital at Mission Santa Catalina (St. Catherines Island). Indian artifacts at the Seven-Mile Bend attest to Guale activity in association with the Spanish mission of San Diego de Satuache. The Guale town and the Spanish mission there were abandoned ca. 1663. The name Ogeechee is Indian in origin and means River of the Uchee, (“seeing far away”) for a village further north on the 245-mile long river. The Seven-Mile Bend site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. |

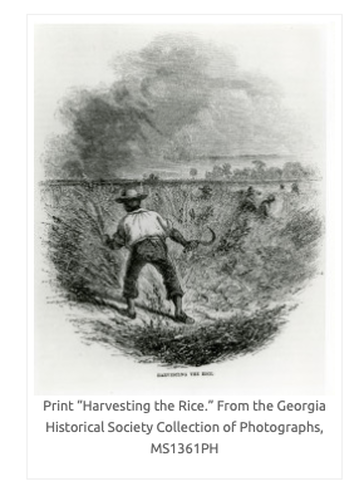

Slavery on Bryan Neck and Georgia

Long before cotton became king, rice ruled the low country. In Georgia, as in South Carolina, a caste of elite planters quickly established itself after Parliament removed the export duty on rice and royal policy lifted limitations on the number of land grants to individuals. Planters grabbed prime rice-growing land by the thousands of acres. Soon fewer than five percent of Georgia landholders owned twenty percent of the land – a situation the founding Trustees had hoped to prevent. The popularity of the labor intensive crop led to a heavy dependence on slave labor. Soon slaves outnumbered whites in the coastal low country. After the slaves harvested the rice, the Atlantic trade system carried it to locations as far away as South America and Europe.

The rice country slave system initially took after the structure employed in the West Indies. It resembled a harsh gang system of long, hard days in marshy fields and a whip-bearing overseer close behind. Because of slave resistance, this form gave way to a more lenient task system which allowed slaves to have time to themselves once they completed their given tasks. Getting to the fields early and working hard allowed the slaves to enjoy time together later in the day and tend their own gardens and livestock. Under this structure, imported slaves saved many of their traditions and language. They adapted and combined their diverse ways into an amalgamated “Gullah” culture and speech. Gullah culture formed the basis for many slave communities. A significant one existed in Liberty County. Click here for more information from the Georgia Historical Society.

The rice country slave system initially took after the structure employed in the West Indies. It resembled a harsh gang system of long, hard days in marshy fields and a whip-bearing overseer close behind. Because of slave resistance, this form gave way to a more lenient task system which allowed slaves to have time to themselves once they completed their given tasks. Getting to the fields early and working hard allowed the slaves to enjoy time together later in the day and tend their own gardens and livestock. Under this structure, imported slaves saved many of their traditions and language. They adapted and combined their diverse ways into an amalgamated “Gullah” culture and speech. Gullah culture formed the basis for many slave communities. A significant one existed in Liberty County. Click here for more information from the Georgia Historical Society.

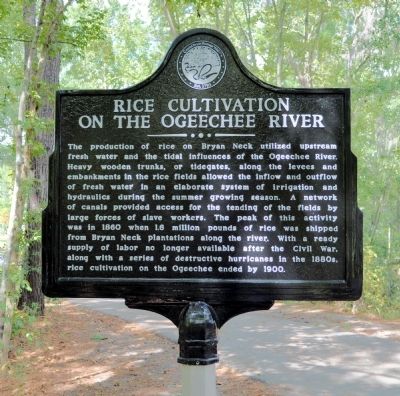

The production of rice on Bryan Neck utilized upstream fresh water and the tidal influences of the Ogeechee River. Heavy wooden trunks, or tidegates, along the levees and embankments in the rice fields allowed the inflow and outflow of fresh water in an elaborate system of irrigation and hydraulics during the summer growing season. A network of canals provided access for the tending of the fields by large forces of enslaved workers. The peak of this activity was in 1860 when 1.6 million pounds of rice was shipped from Bryan Neck plantations along the river. With a ready supply of labor no longer available after the Civil War, along with a series of destructive hurricanes in the 1880s, rice cultivation on the Ogeechee ended by 1900.

Marker is located at 520 Cedar Street, at J. F. Gregory Park in Richmond Hill, Georgia. The marker can be reached from the City Center parking lot. A walking trail begins at a gate at the eastern edge of the City Center parking lot. The marker is approximately 150 feet east of the gate.

William and Ellen Craft: A Daring Escape Story

|

William Craft (1821-1900) and Ellen Craft (1826-1891) were born as enslaved persons near Macon, Georgia. They succeeded in a daring escape from slavery. Ellen, who had light skin, posed as a white man, while William posed as her servant. The Crafts made their way to England with the aid of abolitionist Boston clergyman Theodore Parker. They returned to Georgia after the Civil War and acquired Woodville Plantation in Bryan County, Georgia. Here, they started the Woodville Cooperative Farm School. Read more about their incredible story here: The Great Escape from Slavery of Ellen and William Craft, and in the book Running A Thousand Miles For Freedom.

|

Reconstruction on Bryan Neck

Following the close of the Civil War, the nation began the process of rebuilding itself back into one nation. Under President Andrew Johnson, reconstruction, or the restoration of the seceded states to the United States. In May of 1865, Johnson issued a proclamation of pardon to nearly all those engaged in the war. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified prohibiting slavery in the United States. State’s held conventions to repeal any “Ordinance of Secession,” the 13th Amendment was adopted, and war debt declared null and void. Click here for more about the Civil War in Richmond Hill, Georgia (then Ways Station).

London Harris |

|

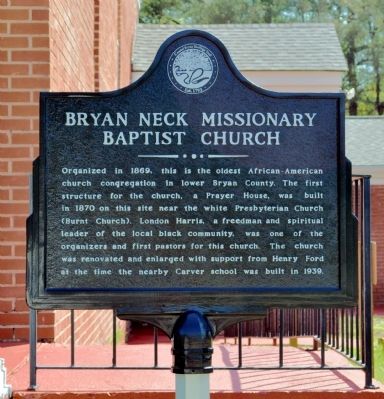

Organized in 1869, the oldest African-American church congregation in lower Bryan County is the Bryan Neck Missionary Baptist Church. The first structure for the church, a Prayer House, was built in 1870 on the same site near the white Presbyterian Church (Burnt Church). London Harris, a freedman and spiritual leader of the local black community, was one of the organizers and first pastors for the church. The church was renovated and enlarged at the time the nearby Carver school was built in 1939 (see below).

|

Marker is located at 16525 Bryan Neck Road, Richmond Hill, Georgia

The Ogeechee Insurrection

"In early December 1868, George Baxley, the new overseer of Southfield Plantation on the Ogeechee Neck in Chatham County, attempted to tear down an old house when Hector Broughton, a worker on the plantation, told him "not to pull that house as [I am] coming back to get [my] forty acres, and [I] want that house." This encounter between Baxley and Broughton precipitated what became known as the 'Ogeechee Insurrection'." Read more here:

The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 85, No. 3 (FALL 2001), pp. 375-397 (23 pages)

More suggested reading:

Dixie Be Damned

Standing Upon the Mouth of a Volcano

After Slavery: Race, Labor, and Citizenship in the Reconstruction South

Exaggerated rumors of an insurrectionary movement afoot on rice plantations in lowcountry Georgia caused great alarm among whites, spurring quasi-military mobilization under the leadership of prominent former Confederates. Upon close examination, the rumors proved mostly unfounded: at the root of disturbances was a confrontation between Black laborers and planters over the terms of labor in the rice fields. This essay examines the role of the national press in circulating sensationalized accounts of the issues at stake during Reconstruction, and concludes that in their attempts to defuse tensions, federal officials encouraged a conflation of labor and race militancy that would ultimately lead to northern disaffection with Reconstruction.

The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 85, No. 3 (FALL 2001), pp. 375-397 (23 pages)

More suggested reading:

Dixie Be Damned

Standing Upon the Mouth of a Volcano

After Slavery: Race, Labor, and Citizenship in the Reconstruction South

Exaggerated rumors of an insurrectionary movement afoot on rice plantations in lowcountry Georgia caused great alarm among whites, spurring quasi-military mobilization under the leadership of prominent former Confederates. Upon close examination, the rumors proved mostly unfounded: at the root of disturbances was a confrontation between Black laborers and planters over the terms of labor in the rice fields. This essay examines the role of the national press in circulating sensationalized accounts of the issues at stake during Reconstruction, and concludes that in their attempts to defuse tensions, federal officials encouraged a conflation of labor and race militancy that would ultimately lead to northern disaffection with Reconstruction.

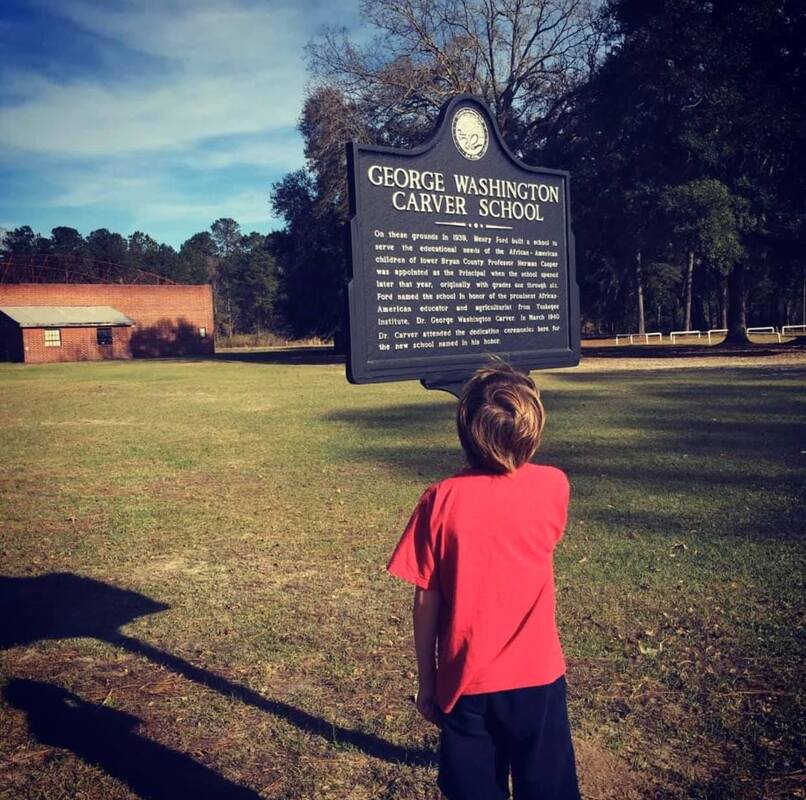

George Washington Carver

|

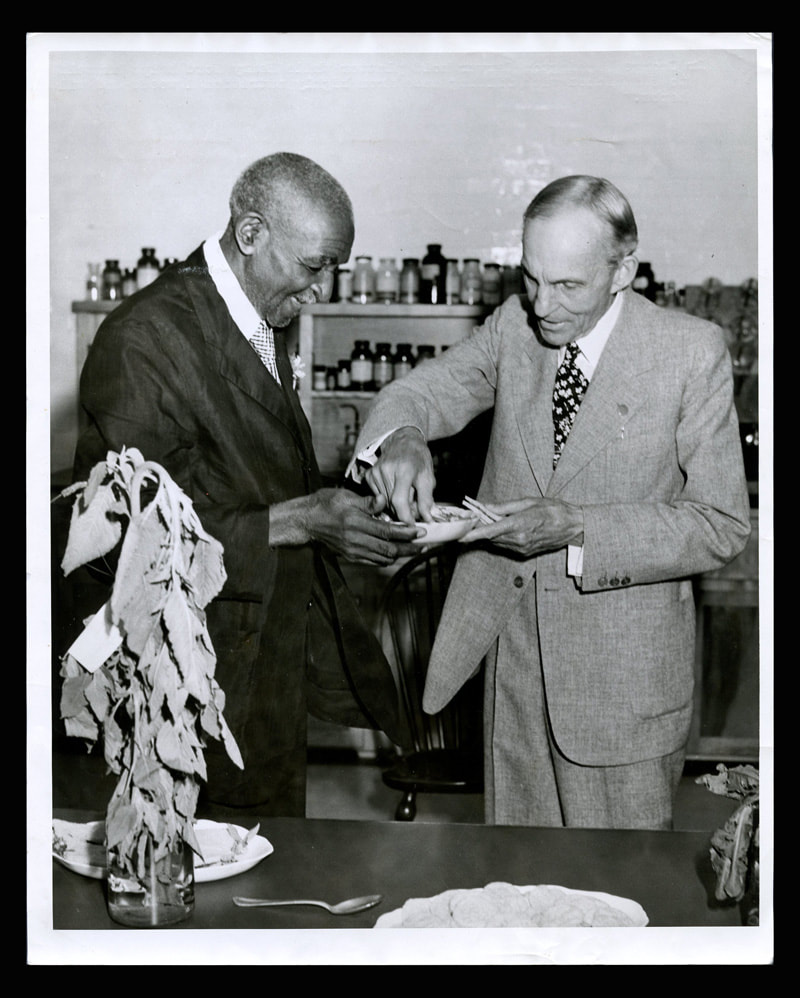

George Washington Carver was an agricultural scientist and inventor who developed hundreds of products using peanuts (though not peanut butter, as is often claimed), sweet potatoes and soybeans. Born an African American enslaved person a year before slavery was outlawed, Carver left home at a young age to pursue education and would eventually earn a master’s degree in agricultural science from Iowa State University. He would go on to teach and conduct research at Tuskegee University for decades, and soon after his death his childhood home would be named a national monument — the first of its kind to honor an African American.

Henry Ford first sought out Carver’s advice in the 1920s, beginning a friendship that lasted until Carver’s death in 1943. Ford was deeply interested in developing alternative energy sources to gasoline and was fascinated by Carver’s work with soybeans and peanuts. The two exchanged visits at Tuskegee and Ford’s Dearborn, Michigan, plants, where they worked together on a series of initiatives. During World War II, the U.S. government asked the pair to develop a soybean-based alternative to rubber during an era of wartime rationing. After weeks of experiments in Michigan in July 1942, Carver and Ford produced a successful replacement using goldenrod. That same year, inspired by collaborations with Carver, Ford demonstrated a newly-designed car with a lightweight body comprised in part from soybeans. Ford also became a key financial backer of the Tuskegee Institute, underwriting many of Carver’s initiatives, and even installing an elevator in Carver’s house to help his increasingly infirm friend move around his Alabama home. Ford’s fellow inventor Thomas Edison was also a fan of Carver. Although Carver later embellished the financial details of the story to reporters, in 1916, Edison unsuccessfully tried to lure Carver away from Tuskegee to become a researcher in Edison’s famed New Jersey laboratory. George Washington Carver | The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation:

|

Nurses Constance Clark and Ella Reed Sams

Nurse Constance Clark and Nurse Ella Reed Sams, cared for hundreds of men, women and children at the Ways Station Health Association, later the Richmond Hill Clinic, operated by Henry Ford during the years of 1930-1951. The two gave vaccinations and treatments for malaria, smallpox, typhoid, hookworm and other illnesses. They also cared for injuries and gave general wellness and cleanliness advice. In addition to working in the local clinic, they regularly traveled to schools, homes and rural areas to treat patients.

The local doctor, Dr. Holton, along with Nurse Clark and Nurse Reed, were seeing hundreds of cases of Malaria in their patients. After a fatality in 1936, Dr. Holton approached Mr. Ford about a better way of helping the 2,000 people who lived in Bryan County. Mr. Ford became very interested in the idea and agreed to fund a plan to eradicate the disease, regardless of the cost.

The first step was to hire an additional 18 nurses for the small clinic, who trained for several weeks. Second, they involved the Georgia State Board of Health. Third, they tested residents and found a large number of people who lived in Bryan County were infected with the disease. Everyone who lived on Mr. Ford’s property was required to begin a five-day treatment of the drug Atabrine. “The nurses went around to every person living in the community and administered Atabrine to every individual - man, woman or child, White or Black. They had to take it or get out. That was the rule,” said Dr. Holton in a 1952 interview. “ No one refused. Patients were retested and treated with a follow up drug until they tested negative.

In addition, Ford undertook an extensive project to drain any standing water in the area to try to eliminate disease-carrying mosquitoes. “We did eradicate it there and we eradicated it completely once and for all,” Holton recalled. “Atabrine is a permanent cure. I might add that partly due the the stimulus of our work there, the State Board of Health has practically eradicated Malaria from the entire state of Georgia. It formerly was the greatest economic and medical factor in the state.”

Read about the project in their own words here:

Oral interview given by Nurse Constance Clark in 1952

Oral interview given by Dr. C. F. Holton in 1952

The local doctor, Dr. Holton, along with Nurse Clark and Nurse Reed, were seeing hundreds of cases of Malaria in their patients. After a fatality in 1936, Dr. Holton approached Mr. Ford about a better way of helping the 2,000 people who lived in Bryan County. Mr. Ford became very interested in the idea and agreed to fund a plan to eradicate the disease, regardless of the cost.

The first step was to hire an additional 18 nurses for the small clinic, who trained for several weeks. Second, they involved the Georgia State Board of Health. Third, they tested residents and found a large number of people who lived in Bryan County were infected with the disease. Everyone who lived on Mr. Ford’s property was required to begin a five-day treatment of the drug Atabrine. “The nurses went around to every person living in the community and administered Atabrine to every individual - man, woman or child, White or Black. They had to take it or get out. That was the rule,” said Dr. Holton in a 1952 interview. “ No one refused. Patients were retested and treated with a follow up drug until they tested negative.

In addition, Ford undertook an extensive project to drain any standing water in the area to try to eliminate disease-carrying mosquitoes. “We did eradicate it there and we eradicated it completely once and for all,” Holton recalled. “Atabrine is a permanent cure. I might add that partly due the the stimulus of our work there, the State Board of Health has practically eradicated Malaria from the entire state of Georgia. It formerly was the greatest economic and medical factor in the state.”

Read about the project in their own words here:

Oral interview given by Nurse Constance Clark in 1952

Oral interview given by Dr. C. F. Holton in 1952

The Vietnam War

Posted: Nov 11, 2019 / 03:44 PM EST / Updated: Nov 11, 2019 / 05:47 PM EST

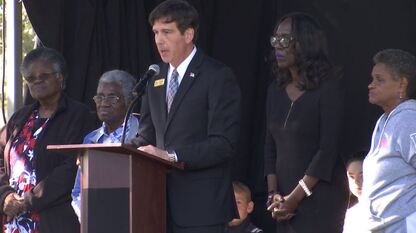

RICHMOND HILL, Ga. (WSAV) — Dozens of veterans and family members visited J.F. Gregory Park Monday morning to pay tribute to those who served — and in some cases, sacrificed their lives for — the United States of America.

City of Richmond Hill Mayor Russ Carpenter led the Veterans Day Ceremony, which included speeches from Carpenter; Col. Scott O’ Neal, who serves as Commander of the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division; and Mr. Al Lipphardt of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) National Council of Administration.

In the back of the city’s ceremony stood the Vietnam Moving Wall, the half-size replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

The wall, which has been in Richmond Hill since last Thursday, lists the names of those who have fallen during service to their country.

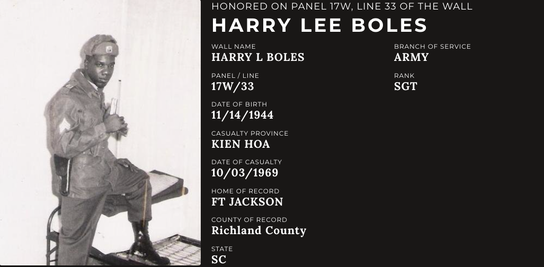

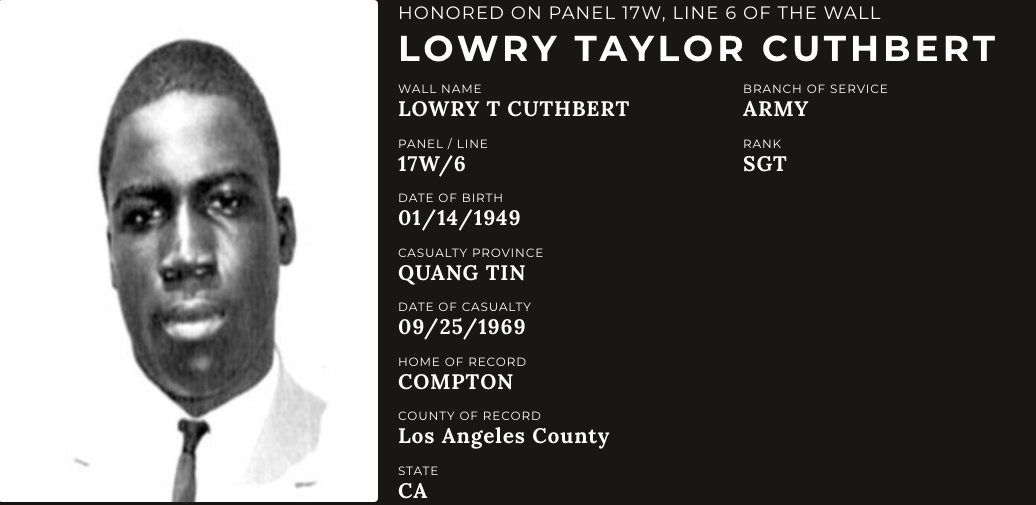

Two of the names listed on the wall are those of Harry Lee Boles and Lowry Cuthbert, two Richmond Hill residents who paid the ultimate sacrifice. They both died serving the U.S. in Vietnam in 1969.

The mayor presented the families of both fallen soldiers with certificates of recognition for the “heroism, courage and sacrifice” of Boles and Cuthbert 50 years ago.

“The saying ‘freedom isn’t free’ is true, it’s not just a catchphrase, it’s not free,” attendee Scott Dexter, the father of a U.S. Marine, told News 3.

“It’s because of the people that have served and are serving that have given their lives, that face the possibility of giving their life every day they serve; it’s because of them that we have what we have.”

RICHMOND HILL, Ga. (WSAV) — Dozens of veterans and family members visited J.F. Gregory Park Monday morning to pay tribute to those who served — and in some cases, sacrificed their lives for — the United States of America.

City of Richmond Hill Mayor Russ Carpenter led the Veterans Day Ceremony, which included speeches from Carpenter; Col. Scott O’ Neal, who serves as Commander of the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division; and Mr. Al Lipphardt of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) National Council of Administration.

In the back of the city’s ceremony stood the Vietnam Moving Wall, the half-size replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

The wall, which has been in Richmond Hill since last Thursday, lists the names of those who have fallen during service to their country.

Two of the names listed on the wall are those of Harry Lee Boles and Lowry Cuthbert, two Richmond Hill residents who paid the ultimate sacrifice. They both died serving the U.S. in Vietnam in 1969.

The mayor presented the families of both fallen soldiers with certificates of recognition for the “heroism, courage and sacrifice” of Boles and Cuthbert 50 years ago.

“The saying ‘freedom isn’t free’ is true, it’s not just a catchphrase, it’s not free,” attendee Scott Dexter, the father of a U.S. Marine, told News 3.

“It’s because of the people that have served and are serving that have given their lives, that face the possibility of giving their life every day they serve; it’s because of them that we have what we have.”