OUR HISTORY

The Georgia Colony

The history of Richmond Hill goes back to the earliest days of the Georgia colony when, in 1733, General James Oglethorpe built Fort Argyle near the confluence of the Ogeechee and Canoochee Rivers to protect the western approaches to Savannah. The legalization of slavery in 1750 and the availability of highly cultivable agricultural bottom land along the Ogeechee River led to rapid settlement in lower St. Philip Parish (Bryan Neck) through the issuance of crown land grants prior to the Revolution.

In 1793, Bryan County was created from Chatham and Effingham Counties, being named in honor of Colonial planter and Revolutionary patriot Jonathan Bryan (1708-1788). The earliest meetings of county officials were held at Strathy Hall Plantation before the local seat of government was moved to Cross Roads at the intersection of the Darien-Savannah Stage Road and the Bryan Neck Road, later the site of Richmond Hill. As the population of the area expanded into Bryan County hinterlands north of the Canoochee River, the county seat was moved again in 1815, this time to Eden, which in 1886 was renamed as the unincorporated township of Clyde.

Cotton is King, Rice is Queen

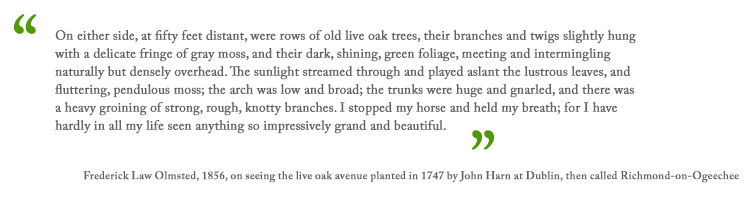

The proximity of the Ogeechee River in the section that later became Richmond Hill was the salient factor in rice evolving as the primary cash crop of the local agricultural economy. The earliest Ogeechee rice plantations in the vicinity (pre-and-post-Revolutionary War) were those of Thomas Savage and his heirs at Silk Hope and of the Harns, followed by the Habershams, at Dublin. Lower Bryan County was the locale of some of the most productive rice and Sea Island cotton plantations of tidewater Georgia in the four decades prior to the Civil War.

The larger rice tracts those managed by the leading slave owners. These included the several plantations of Thomas Savage Clay, the largest being Richmond-on-Ogeechee (formerly Dublin), later managed by his sister, Eliza Caroline Clay. The Clays also operated Tranquilla, Tivoli, and Piercefield, the latter three being largely devoted to the cultivation of provision crops and cotton. Richard James Arnold of Providence, Rhode Island, had two large holdings, Cherry Hill (the rice tract adjacent to Richmond), and White Hall farther downriver. Arnold additionally held several smaller rice tracts, including Orange Grove, Mulberry, Sedgefield, and half of Silk Hope, all within the present town limits of Richmond Hill. George Washington McAllister planted rice at Strathy Hall and cotton at Genesis Point; the Maxwell family cultivated various holdings throughout Bryan Neck, chiefly in the vicinity of the Belfast River, and Charles W. Rogers was the section's largest cotton planter at Kilkenny on the lower end of the neck. Of these, Richard James Arnold was the most prominent. According to the U.S. agricultural census of 1860, he owned 11,000 acres in lower Bryan County, with 195 slaves cultivating the lower Ogeechee's largest rice yields supplemented by two other primary staples, sugar cane and Sea Island cotton. Arnold's rice crop in 1859 was listed as 665,000 pounds, by far the largest of the local planters.

The agricultural economy of the section was enhanced by the completion of thee Savannah-Ogeechee Canal in 1830 near Kings Ferry. The Savannah, Albany, and Gulf Railroad was built to link Savannah with southwest Georgia. Tracks were laid across the Ogeechee and into Bryan Neck in 1856, traversing the Silk Hope rice fields of Richard J. Arnold and William J. Way. The station depot was designated Ways No. 1 1/2. A settlement developed there between the tracks and the Cross Roads and came to be known as Ways Station, the forerunner of Richmond Hill.

Civil War

In 1861, in response to Union naval threats to the southern approaches of Savannah, Fort McAllister was built on the Ogeechee at Genesis Point, several miles southeast of Ways Station. This earthwork fortification repelled seven Union naval attacks in 1862 and 1863, including assaults by heavily armed Monitor class gunboats. The CSS Rattlesnake (former CSS Nashville), a Confederate blockade-runner, sought refuge in the Ogeechee River but was burned and sunk in the river near Fort McAllister by Union gunfire in February 1863. In December 1864, Bryan Neck was invaded by elements of the right wing of Gen. William T. Sherman's forces as they neared Savannah. In a short, intense battle, Fort McAllister was overwhelmed by superior Union forces, which had crossed the river at Kings Ferry then marched down Bryan Neck to assault the fort from its largely unprotected landward side.

Reconstruction

After the Civil War, emancipated African Americans on Bryan Neck began to purchase their own land from the heirs of plantation owners. Amos Morel, the head enslaved worker for Richard J. Arnold, became the most prominent freedman of the section as well as the largest landowner. New settlements of the former slaves were established at Brisbon, Rabbit Hill, Port Royal, Oak Level, Fancy Hall, and Daniel Siding. Blacks worked for wages at the revived Ogeechee River plantations, and the section prospered until hurricanes in the 1890s forced the abandonment of the rice industry in tidewater Georgia. Later many African Americans found employment in the local lumber industry. In 1901, the Hilton Dodge Lumber Company opened a sawmill and timber port on the Belfast River, activity that continued until 1916.

Henry Ford Arrives

In 1925, Henry Ford of Dearborn, Michigan, began purchasing land on Bryan Neck, eventually owning about 85,000 acres on both sides of the Ogeechee. Ford was interested in the social and agricultural improvement of the area around Ways Station, then one of the most impoverished places in coastal Georgia. Ford began agricultural operations; provided housing and medical facilities; and built churches, a community center, and schools for blacks and whites. He developed a sawmill, vocational trade school, improved roads, and other infrastructure and generally brought Ways Station into the 20th century. In 1941, the federal government condemned 105,000 acres of sparsely settled land in the center of Bryan County for the Camp Stewart U. S. Army training base. The coming of Camp Stewart necessitated the relocation of all civilian residents of the middle section of Bryan, including the small communities of Letford, Roding, and the county seat at Clyde. Many of these displaced residents built new homes in Richmond Hill. The name of the town is changed from Ways Station to Richmond Hill in Ford's honor.

Henry Ford died in 1947, followed in 1951 by the sale of his Richmond Hill plantation, in addition to his other holdings on Bryan Neck, to the International Paper Company. The Ford operations at Richmond Hill were officially suspended June 30, 1952.

Richmond Hill Becomes a City

On March 3, 1962, the township of Richmond Hill was incorporated through an act of the Georgia Legislature. The first city elections were held, with the first mayor (L. C. Gill) taking office in March 1963. The population of the town at the time of incorporation was about 500 residents. Richmond Hill remained a quiet, rural community built along both sides of U. S. Highway 17 until rapid suburban growth from nearby Savannah began in the 1980s.

Buddy Sullivan in association with the Richmond Hill Historical Society, Excerpts from Images of America, Richmond Hill (Arcadia Publishing, 2006)

In 1793, Bryan County was created from Chatham and Effingham Counties, being named in honor of Colonial planter and Revolutionary patriot Jonathan Bryan (1708-1788). The earliest meetings of county officials were held at Strathy Hall Plantation before the local seat of government was moved to Cross Roads at the intersection of the Darien-Savannah Stage Road and the Bryan Neck Road, later the site of Richmond Hill. As the population of the area expanded into Bryan County hinterlands north of the Canoochee River, the county seat was moved again in 1815, this time to Eden, which in 1886 was renamed as the unincorporated township of Clyde.

Cotton is King, Rice is Queen

The proximity of the Ogeechee River in the section that later became Richmond Hill was the salient factor in rice evolving as the primary cash crop of the local agricultural economy. The earliest Ogeechee rice plantations in the vicinity (pre-and-post-Revolutionary War) were those of Thomas Savage and his heirs at Silk Hope and of the Harns, followed by the Habershams, at Dublin. Lower Bryan County was the locale of some of the most productive rice and Sea Island cotton plantations of tidewater Georgia in the four decades prior to the Civil War.

The larger rice tracts those managed by the leading slave owners. These included the several plantations of Thomas Savage Clay, the largest being Richmond-on-Ogeechee (formerly Dublin), later managed by his sister, Eliza Caroline Clay. The Clays also operated Tranquilla, Tivoli, and Piercefield, the latter three being largely devoted to the cultivation of provision crops and cotton. Richard James Arnold of Providence, Rhode Island, had two large holdings, Cherry Hill (the rice tract adjacent to Richmond), and White Hall farther downriver. Arnold additionally held several smaller rice tracts, including Orange Grove, Mulberry, Sedgefield, and half of Silk Hope, all within the present town limits of Richmond Hill. George Washington McAllister planted rice at Strathy Hall and cotton at Genesis Point; the Maxwell family cultivated various holdings throughout Bryan Neck, chiefly in the vicinity of the Belfast River, and Charles W. Rogers was the section's largest cotton planter at Kilkenny on the lower end of the neck. Of these, Richard James Arnold was the most prominent. According to the U.S. agricultural census of 1860, he owned 11,000 acres in lower Bryan County, with 195 slaves cultivating the lower Ogeechee's largest rice yields supplemented by two other primary staples, sugar cane and Sea Island cotton. Arnold's rice crop in 1859 was listed as 665,000 pounds, by far the largest of the local planters.

The agricultural economy of the section was enhanced by the completion of thee Savannah-Ogeechee Canal in 1830 near Kings Ferry. The Savannah, Albany, and Gulf Railroad was built to link Savannah with southwest Georgia. Tracks were laid across the Ogeechee and into Bryan Neck in 1856, traversing the Silk Hope rice fields of Richard J. Arnold and William J. Way. The station depot was designated Ways No. 1 1/2. A settlement developed there between the tracks and the Cross Roads and came to be known as Ways Station, the forerunner of Richmond Hill.

Civil War

In 1861, in response to Union naval threats to the southern approaches of Savannah, Fort McAllister was built on the Ogeechee at Genesis Point, several miles southeast of Ways Station. This earthwork fortification repelled seven Union naval attacks in 1862 and 1863, including assaults by heavily armed Monitor class gunboats. The CSS Rattlesnake (former CSS Nashville), a Confederate blockade-runner, sought refuge in the Ogeechee River but was burned and sunk in the river near Fort McAllister by Union gunfire in February 1863. In December 1864, Bryan Neck was invaded by elements of the right wing of Gen. William T. Sherman's forces as they neared Savannah. In a short, intense battle, Fort McAllister was overwhelmed by superior Union forces, which had crossed the river at Kings Ferry then marched down Bryan Neck to assault the fort from its largely unprotected landward side.

Reconstruction

After the Civil War, emancipated African Americans on Bryan Neck began to purchase their own land from the heirs of plantation owners. Amos Morel, the head enslaved worker for Richard J. Arnold, became the most prominent freedman of the section as well as the largest landowner. New settlements of the former slaves were established at Brisbon, Rabbit Hill, Port Royal, Oak Level, Fancy Hall, and Daniel Siding. Blacks worked for wages at the revived Ogeechee River plantations, and the section prospered until hurricanes in the 1890s forced the abandonment of the rice industry in tidewater Georgia. Later many African Americans found employment in the local lumber industry. In 1901, the Hilton Dodge Lumber Company opened a sawmill and timber port on the Belfast River, activity that continued until 1916.

Henry Ford Arrives

In 1925, Henry Ford of Dearborn, Michigan, began purchasing land on Bryan Neck, eventually owning about 85,000 acres on both sides of the Ogeechee. Ford was interested in the social and agricultural improvement of the area around Ways Station, then one of the most impoverished places in coastal Georgia. Ford began agricultural operations; provided housing and medical facilities; and built churches, a community center, and schools for blacks and whites. He developed a sawmill, vocational trade school, improved roads, and other infrastructure and generally brought Ways Station into the 20th century. In 1941, the federal government condemned 105,000 acres of sparsely settled land in the center of Bryan County for the Camp Stewart U. S. Army training base. The coming of Camp Stewart necessitated the relocation of all civilian residents of the middle section of Bryan, including the small communities of Letford, Roding, and the county seat at Clyde. Many of these displaced residents built new homes in Richmond Hill. The name of the town is changed from Ways Station to Richmond Hill in Ford's honor.

Henry Ford died in 1947, followed in 1951 by the sale of his Richmond Hill plantation, in addition to his other holdings on Bryan Neck, to the International Paper Company. The Ford operations at Richmond Hill were officially suspended June 30, 1952.

Richmond Hill Becomes a City

On March 3, 1962, the township of Richmond Hill was incorporated through an act of the Georgia Legislature. The first city elections were held, with the first mayor (L. C. Gill) taking office in March 1963. The population of the town at the time of incorporation was about 500 residents. Richmond Hill remained a quiet, rural community built along both sides of U. S. Highway 17 until rapid suburban growth from nearby Savannah began in the 1980s.

Buddy Sullivan in association with the Richmond Hill Historical Society, Excerpts from Images of America, Richmond Hill (Arcadia Publishing, 2006)

Tell the Full Story

We believe all Americans deserve to see their history in the places that surround us. Yet just a small fraction of the sites on the National Register of Historic Places represent women and people of color. As a nation, we have work to do to fill in the gaps of our cultural heritage.

That’s why the National Trust for Historic Preservation shines a long-overdue spotlight on generations of trailblazers by saving the places where they raised their voices, took their stands, and found the courage to change the world

Thanks to the support of people like you, we can tell a fuller American story. It’s a story that does justice to the contributions of women, people of color, and all Americans in shaping our nation and leading us forward. And it’s a story that stirs us all to take pride in our shared heritage and inspires us to create an even more perfect union for generations to come. Click here for more information.

That’s why the National Trust for Historic Preservation shines a long-overdue spotlight on generations of trailblazers by saving the places where they raised their voices, took their stands, and found the courage to change the world

Thanks to the support of people like you, we can tell a fuller American story. It’s a story that does justice to the contributions of women, people of color, and all Americans in shaping our nation and leading us forward. And it’s a story that stirs us all to take pride in our shared heritage and inspires us to create an even more perfect union for generations to come. Click here for more information.